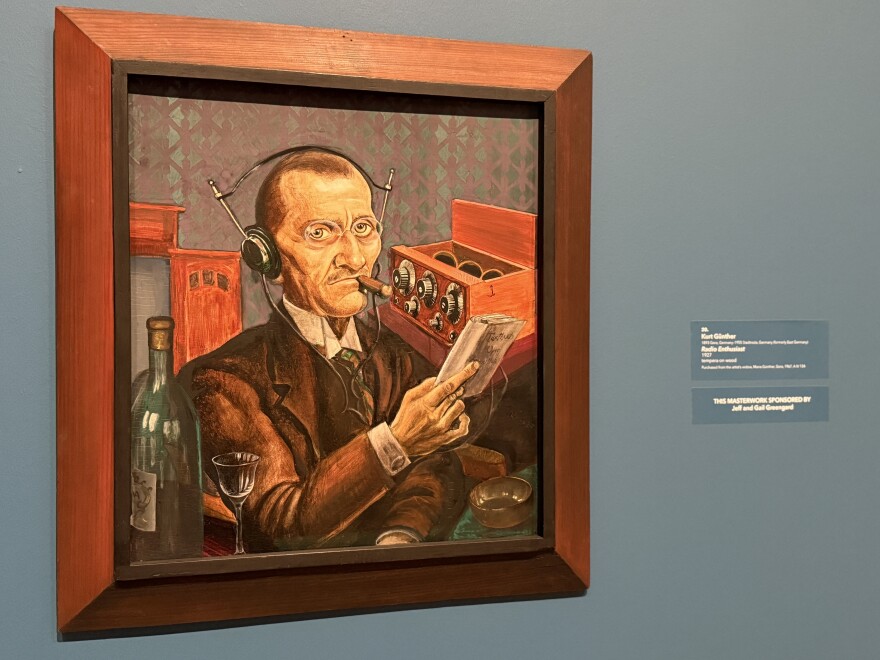

A landmark exhibition of 20th century German art at the Albuquerque Museum presents works infused with the zeitgeist of their time, yet whose themes speak to our own troubled era.

“Modern Art and Politics in Germany 1910–1945: Masterworks from the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin,” is making just three stops in the United States. The exhibition comes to New Mexico after appearing at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, and is scheduled to travel to the Minneapolis Institute of Art after its run in Albuquerque concludes January 4.

Many of the works were featured in an exhibit created by the Nazis in the 1930s to show what they dubbed “degenerate art.”

Albuquerque Museum Director Andrew Connors said the German curators of the exhibition wanted the rest of the world to experience these works, in part to underscore the lessons that come to us from those decades in German history.

“Many academics and intellectuals in Germany feel it's crucial to tell the story of what happened in their country, with the hope that no other country would follow along in that same path,” Connors said.

The paintings and sculptures on display take the viewer from the height of the German Empire, followed by World War I, the Weimar Republic, Nazi rule, and finally World War II and the defeat of the Third Reich.

It includes works by German artists Max Beckmann, George Grosz, Hannah Höch, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, along with the Swiss-born German artist Paul Klee. Reflecting Berlin’s interlude as an international center of artistic innovation, it also features European artists of the time, including Giorgio de Chirico, Salvador Dalí, Wassily Kandinsky, and Pablo Picasso.

Visitors move chronologically through artistic movements. Those include Expressionism, developed during the Empire, and New Objectivity, a Weimar-era movement reacting against Expressionism. That section includes Christian Schad’s portrait “Sonja,” which Connors said is frequently called the German “Mona Lisa.”

“She has an expression that seems completely implacable,” he said. “We really don’t know exactly what she’s feeling, but she’s seated at a table at a nightclub with the pianist in the upper right-hand corner, a bottle of French champagne behind her, and all of her makeup and Camel cigarettes out on the table in front of her, reflecting her comfort in being a modern woman in society.”

Sonja’s boldly unstudied elegance reflects the fashion, and the ideological mood, of the time. Germany was a vortex for various incompatible artistic and political forces on a collision course.

“This exhibition tells that trajectory in a very powerful way with visual art objects that are not just illustrations of the time, but are visceral representations of the horrors, the terrors and the hopes for triumph in Germany during this time period,” Connors said.

The works on display come from a vast diversity of artistic styles, social contexts, and ideological perspectives.

Curt Querner’s self-portrait shows his frustration and anger as he glares out from the canvas. Connors said he created the portrait immediately after returning from a Communist Party meeting shut down by the Nazis where 10 of his colleagues were executed and 17 more were wounded.

“So he came back to his studio and painted this self portrait with this face of conviction and anger, and clutched between his fingers is a stinging nettle to show his perseverance and his ability to resist pain and outside influence, to move away from the cause that he felt was so crucial,” Connors said.

Other sections focus on abstract and avante-garde art, as well as works created in response to war and the rise of totalitarianism. Some of the artists represented in the exhibition resisted militarism and authoritarianism, and eventually fled into exile. Kathe Kollwitz created a small bronze called “Tower of Mothers.” A group of women is gathered together and in between their dresses are the heads of children they are trying to protect.

“So the ‘Tower of Mothers’ are protecting the next generation from all of the horrors of society, probably the horrors of totalitarianism, the horrors of warfare,” Connors said. “Kathe Kollwitz lost her son in World War I. So she was dedicated to fighting against the tyranny of militarism and the rise of totalitarian states and wars that she felt were innately unjust.”

Others worked with only art in mind, while some supported reactionary elements. Even works that seemingly have nothing to do with politics are in the show. The rise of modernity, expressed in things like abstraction and the Bauhaus movement, attracted Nazi ire. Adolf Hitler was a failed artist before he entered politics and The Guardian reports his work was dismissed by contemporary art critics who preferred modern styles. Quite a few artists had their works confiscated from museums and galleries and ridiculed in the infamous Entartete Kunst, or Degenerate Art, exhibition in Munich in 1937.

“This exhibition reflects the way that the Nazis understood the power of art and the way that artists frequently could get to the truth of a situation in a way that many others couldn't,” Connors said. “When totalitarian regimes find that there is a voice out there that is encouraging people to think expansively and to think on their own and come up with their own conclusions, that's exactly when those totalitarian leaders say these people are dangerous to our society.”

Sonja, the model from the cabaret portrait, was actually named Albertine Gimpel. When the Nazis took power in 1933, she lost her job because she was Jewish. An American-born painter, Franz Herda, managed to help hide Gimpel for the duration of the war. She survived, and moved to New York after the war ended. But millions like her did not survive.

Modern Art and Politics in Germany 1910–1945: Masterworks from the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin is at the Albuquerque Museum through January 4.