Although deaths from cancer have gone down over the last couple decades, the disease remains one of the leading causes of death in the United States, just as it has for the last 75 years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. An outright cure probably won’t materialize any day soon, but researchers at the University of New Mexico are on the cutting edge of treatment options that show promising results.

Dr. Sarah Adams is a professor of gynecological oncology who has been working with Associate Professor in Internal Medicine Rita Serda to develop a therapeutic cancer vaccine they jokingly refer to as the “Zombie Vaccine.”

Essentially, Adams said, they encase dead cancer cells in silica, which can then be presented to the immune system as completely harmless, but perfect structural replicas of what the immune system should target.

“So still the same on the outside, dead on the inside,” Adams said, “kind of like a zombie.”

Cancer vaccines can be either preventative by stopping it before it starts, or therapeutic by fighting active tumors. And they’re quickly becoming one of the most widely researched and potentially powerful tools available to doctors.

The “Zombie Vaccine” is specifically crafted for each individual using the patient's own cancer cells. That means the treatment ostensibly can be used on any type of cancer where doctors are able to actually access the tumor to get sample cells.

In testing so far, Serda said it has shown incredible promise.

“We can actually wipe out the cancer in our preclinical studies,” she said. “We can eliminate it completely and we can actually block recurrence, too, when we rechallenge the mice with more cancer later.”

Adams said cancer cells use a variety of mechanisms to avoid immune detection, and in some environments the immune response can actually be beneficial to cancer cells.

“The same kinds of molecules that promote wound healing and tissue regeneration,” Adams said, “can promote cancer growth in some situations.”

So, to trigger the right kind of immune response, researchers not only encase the cancer cells in silica, Serda said they have also been able to alter them with microbial molecules on the cancer cells’ surface, which act as little flags that trigger the immune system to attack the cancer cells.

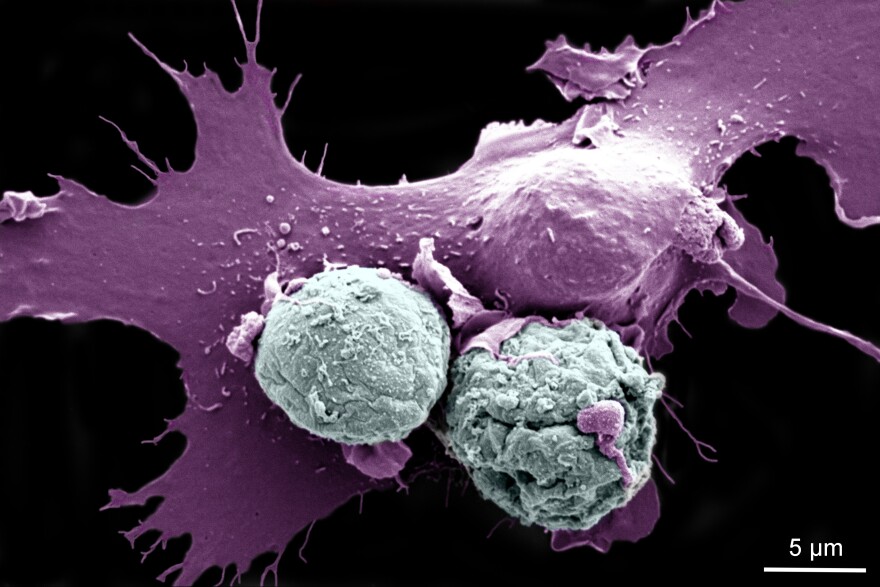

“One of the first things that we did was we looked at live cancer cells, and the immune cells were ignoring them, but when we modified them with silica and microbial molecules, then they started engulfing and eating them immediately,” she said. “So it was a huge change.”

Serda said they have developed the vaccine so that it won’t have to be refrigerated, which will help when distributing to remote areas, or countries where electrical power is limited.

Serda and Adams have been working on the vaccine for six years. They started testing on bacteria, and are now testing it against actual human cancer cells in humanized mice, which are mice that have been altered with a human-like immune symptom.

The next steps, they said, are to speak with the FDA and prepare for phase one of clinical trials.

Treating cancer once it’s actually growing is one thing, but another model with head-turning promise is stopping cancer before it even starts. That’s exactly what Michelle Ozbun and Jason McConville have been working on in treating cancers caused by the Human Papillomavirus, or HPV.

It’s one of the most common viruses in the United States, with 13 million people contracting it every year, according to the CDC. Although most cases will go away on their own within two years, HPV accounts for nearly 5% of all cancers worldwide and can cause several types of cancer.

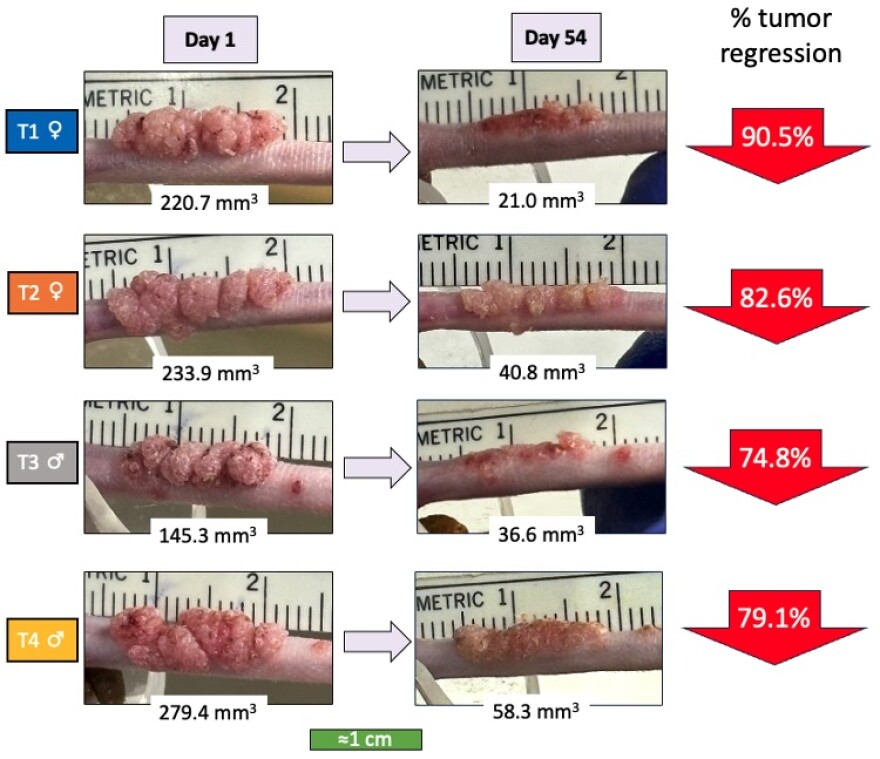

Ozbun, the Maralyn S. Budke Endowed Professor of Viral Oncology at UNM, said HPV causes warts, which are basically just benign tumors, but HPV can alter the warts to become malignant. Ozbun found that an existing medication used to treat some skin cancers was highly successful at treating HPV warts. Not only did the warts shrink, but they did not regrow either.

However, there was one problem — the drug was toxic when given orally.

“So I started talking to people, ‘it would be great if we could put this on the wart, and then it wouldn't be systemic and it might not be as toxic’” she said. “And I was talking to some colleagues in the College of Pharmacy, and they said, ‘Oh, you need to talk to Jason, because he does topicals.’”

McConville, an associate professor of pharmaceutics, suggested dissolving the drug in a penetration enhancer, and they developed several formulations in different types of carriers, like gels or a spray.

Ozbun and McConville said although there are vaccines for HPV itself, this could be used by people who have already contracted HPV to eliminate warts and ensure they don’t turn into cancer, and would be effective on several types of cancer.

“That's our goal,” Ozbin said, “to make a cancer-free New Mexico that extends to the United States.”

“Obviously,” McConville said, “cervical cancer is one of the highest occurring cancers there is. But also this oropharyngeal cancer related to HPV infection is on the rise.”

The treatment has been shown to be highly effective in pre-clinical trials, and the team is using a $2.7 million grant from the National Cancer Institute to continue their research. They’re also starting a small business to take advantage of other types of funding, and to fast-track the formulation for further trials, but even with that, they expect it won’t be available for at least 5 to10 years.

Support for this coverage comes from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. While UNM holds KUNM’s broadcasting license, it has no editorial input on our stories.