Away from any cities or streetlights, the nights here at Chaco Culture National Historic Park are dark. Looking up, it takes a little longer than usual to spot even the most familiar constellations. That’s because there are so many more stars visible across Orion’s shoulders or surrounding Gemini’s twins.

The skies here are so clear that the park has been named an International Dark Sky Park.

But the modern world is encroaching.

On a hilltop about 10 miles outside the park, two flames—and maybe a third?—are visible on the dark horizon.

They’re flares from new oil wells.

“You head down, even on a relatively dark night, (through) Farmington, Bloomfield, Aztec, there’s lots of light, (and you) head down to the Lybrook, Counselor area. It’s really dark, and all of sudden, you see these five fireballs. It’s just crazy,” says Mike Eisenfeld, New Mexico Energy Coordinator with the nonprofit San Juan Citizens Alliance.

“I think that a lot of the flares have been along the (US Highway) 550 corridor and you hear a lot of people kind of going ‘What the heck is that? I couldn’t believe it,’” he says.

Eisenfeld doesn’t want to see more flares around Chaco or nearby, on the eastern Navajo Nation. And along with other groups, the San Juan Citizens Alliance has sued the federal government, asking it to stop approving new wells near the park until there are more studies.

The groups are worried about how development will affect Chaco, as well as water supplies and local communities. But a federal judge denied their request last month.

Looking across a narrow valley near Lybrook, New Mexico, Eisenfeld watches two flares in the distance. He worries about the methane – the natural gas – that’s wasted when it’s flared or venting into the air.

“It has a huge visual impact, even more so, I think it’s just sort of a sad result of our inability to think things through a little bit more thoroughly,” he says.

He’s talking about the gas that’s wasted when it’s flared off.

During normal drilling operations, workers release natural gas from new wells to clear out impurities and also so that gases don’t build up and cause a dangerous blowout.

“That’s our product, that's what we sell, so we don't want to waste that either, through venting or flaring or leakage,” says Steve Henke, who directs the New Mexico Oil and Gas Association.

He adds that that long-term flaring happens because there isn’t pipeline capacity for the gas.

“We’ve taken a lot of steps over the last decade, through new technology, retrofit monitoring, to understand the sources of fugitive methane and to mitigate that,” he says.

Now, the industry’s going to have to do even more. In August, the US Environmental Protection Agency released draft rules that call for methane emissions to be cut by about 40 percent.

Methane is a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change and the Southwest’s warming trend.

Henke says that anytime new regulations come out, there’s concern about whether they’ll actually benefit the environment. And not harm industry.

“We hope that EPA would work with us to understand what economic mitigation looks like to maintain the viability of the industry,” he says.

But Jon Goldstein says that tightening things up will cut pollution from methane. And benefit industry, not hurt it.

Goldstein is a senior policy manager with the Environmental Defense Fund. Last summer, the nonprofit released a study which found that companies drilling on federal and tribal lands were losing more than $350 million a year.

“Every molecule of gas that's escaping through a leak and causing pollution or just being burned off with a flare, is a molecule that’s not being sold,” he says, “and taxpayers can't see royalty and revenue from it, tribes can't see the revenue from it, the oil companies themselves can't earn the revenue from it.”

According to their report, about $100 million worth of gas was wasted in 2013 just in New Mexico.

The losses are due to flaring, venting, and things like leaky pipes and old infrastructure. These are problems that can be fixed, Goldstein says.

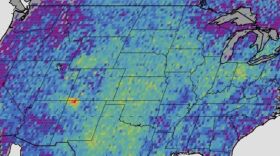

Fixing this problem isn’t just a local issue. It’s related to climate change. Goldstein points out that NASA and other scientists are studying unusually high methane concentrations in the Four Corners area.

“And then you look at this new report and see there’s a big source of this pollution right there in the San Juan Basin,” he says. “You put two and two together and say, ‘Now well, maybe we should be addressing this aggressively.’”

The EPA’s proposed rule is currently open for public comment – and could be finalized next year.

***

Funding for KUNM’s new series Drilling Deep comes from the New Venture Fund. Find out more on our website, KUNM dot org - under News.